Even those with incomes have less “wealth”

Year after year, federal spending on poverty programs has been going up, but we still see more and more people who have no margin to guard against unexpected expenses or job loss. At the same time, for different reasons, Americans who are not impoverished have seen their wealth decline sharply. In this Brookings Podcast video interview, Ron Haskings discusses poverty in America.

Child Poverty and Deprivation Concerns

Report Card 10, from UNICEF’s Office of Research, looks at child poverty and child deprivation across the industrialized world, comparing and ranking countries’ performance. This international comparison, says the Report, proves that child poverty in these countries is not inevitable, but policy susceptible – and that some countries are doing much better than others at protecting their most vulnerable children.

“The data reinforces that far too many children continue to go without the basics in countries that have the means to provide,” said Gordon Alexander, Director of UNICEF’s Office of Research. “The report also shows that some countries performed well – when looking at what is largely pre crisis data – due to the social protection systems that were in place. The risk is that in the current crisis we won’t see the consequences of poor decisions until much later.”

“The report makes clear that some governments are doing much better at tackling child deprivation than others,” said Mr Alexander. “The best performers show it is possible to address poverty within the current fiscal space. On the flip side, failure to protect children from today’s economic crisis is one of the most costly mistakes a society can make.”

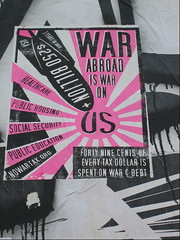

Is Rampant Military Spending Responsible?

More than half of every dollar Americans pay into taxes goes toward military spending, according to an analysis in an Al-Jazeera video featuring a conversation between radio host Dennis Bernstein and journalist Dave Lindorff.

“People have to realize that 53 cents of every dollar that they are paying into taxes is going to the military,” Lindorff says. “It’s an astonishing figure. There is an enormous, enormous amount of money being blown on war and killing and destruction.”

Of the proposed $3 trillion budget, Lindorff says, $717 billion would be allocated to the Pentagon budget; a $158 billion “contingency fund” would be used for military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan; $40 billion in “black box” intelligence spending.

“They never tell us how much they spend on the CIA, NSA and DIA, and all these different intelligence activities, which are all war-related,” he says. An error in testimony about two years ago an error in Congressional testimony led to the revelation that the covert intelligence budget was around $37 billion, Lindorff says, adding that he suspects the budget is really closer to $60 billion or $70 billion.

Poverty Impacts Life Expectancy

Despite modest gains in lifespan over the past century, the United States still trails many of the world’s countries when it comes to life expectancy, and its poorest citizens live approximately five years less than more affluent persons, according to a new study from Rice University and the University Colorado at Boulder.

The study, “Stagnating Life Expectancies and Future Prospects in an Age of Uncertainty,” used time-series analysis to evaluate historical data on U.S. mortality from the Human Mortality Database. The study authors reviewed data from 1930 through 2000 to identify trends in mortality over time and forecast life expectancy to the year 2055. Their research will be published in an upcoming issue of Social Science Quarterly.

Although the researchers found that the U.S. can expect very moderate gains in coming years (less than an additional three years through 2055), the U.S. still trails its developed counterparts in life expectancy. For example, the average life expectancy in the U.S. for a person born today is is 78.49, which is significantly lower than people born in Monaco, Macau and Japan, which have the three highest life expectancies (89.68, 84.43 and 83.91 years, respectively). In addition, the most deprived U.S. citizens tend to live five years less than their more affluent countrymen, according to Justin Denney, Rice assistant professor of sociology, who was principal author for the study.

Denney said that in 1930, average life expectancy in the United States was 59.85. By 2000, it rose to 77.1 years. “But when broken down, these numbers show that those gains were mostly experienced between 1930 the 1950s and 1960s,” he said. “Since that time, gains in life expectancy have flattened out.

The Ugly Side of Inequality

“During periods of expansion in length of life, a similar expansion has occurred between more and less advantaged groups – the rich get richer, the poor get poorer, inequality grows and life expectancy is dramatically impacted,” Denney said. “And despite disproportionate spending on health care, life expectancy in the U.S. continues to fall down the ladder of international rankings of length of life. It goes to show that prosperity doesn’t necessarily equal long-term health.”

Denney said many of the chronic conditions that have led to smaller gains in life expectancy are more easily treated when people are more financially stable. He said the study shows “the ugly side of inequality,” and he hopes it will draw attention to the fact that more needs to be done to address stagnating life expectancies in the U.S. and eliminate inequalities in the U.S.

“Even in uncertain times, it is important to look forward in preparing for the needs of future populations,” Denney said. “The results presented here underscore the relevance of policy and health initiatives aimed at improving the nation’s health and reveal important insight into possible limits to mortality improvement over the next five decades.”